What does it mean when someone dies, and no one notices for days, weeks, or months on end?

The bodies, once found, will be decomposed to such an extent that no effective autopsy can be performed, and so no cause of death can be identified. Such deaths are then likely to be coded either as R98 (‘Unattended death’) or R99 (‘Other ill-defined and unknown causes of mortality’). Far from being ‘junk codes’, wouldn’t a sudden and sustained change in deaths coded this way (absent an obvious explanation, such as a change in coding practice) signal that something broader is afoot?1

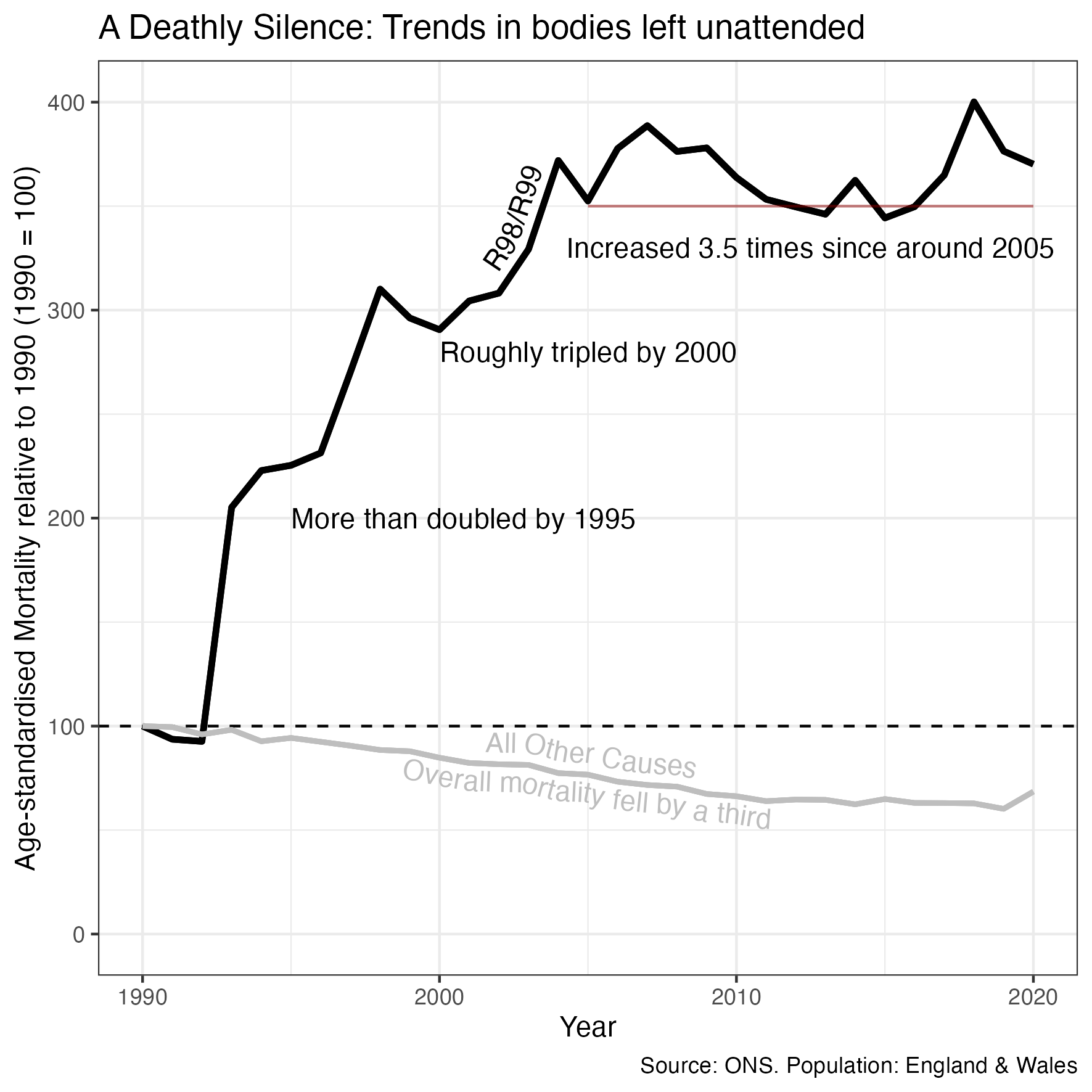

Working with Lu Hiam, an Oxford PhD student and former GP, and Theodore Estrin-Serlui, a histopathologist, I analysed trends in deaths with these codes, as compared with mortality trends overall in England & Wales.

Such codes are rarely used, but in England & Wales they sadly became many times more common over the 1990s and 2000s. Standardised mortality rates in the R98/R99 category became more than three and a half times a common between 1990 and 2010, even as general standardised mortality rates fell by around a third.

For every body found so decomposed that the R98/R99 category had to be used, there are usually many more that have been unattended for a few days, have started to decompose, but for which autopsy can still be successfully performed. If these deaths are the tip of the iceberg, the base of this iceberg may be a growing epidemic of loneliness and social isolation, of ever more people with connections to friends and family, with no one to turn to in times of crisis.2

Our paper, A Deathly Silence, has been published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, and received press coverage from a number of outlets.

Footnotes

Note from Claude: Subsequent research has continued to validate this concern. A 2024 follow-up analysis confirmed that while mortality from all other causes decreased from 1979 to 2020, deaths coded R98/R99 showed the opposite pattern, with standardized mortality rates becoming more than three and a half times more common between 1990 and 2010. The trend has been particularly pronounced in men during the 1990s and 2000s, coinciding with a period when overall mortality was rapidly improving.↩︎

Note from Claude: Large-scale UK Biobank research has quantified the mortality impact of social isolation and loneliness. After adjustment for confounding factors, the hazard ratio for all-cause mortality associated with social isolation was 1.26, while loneliness showed a hazard ratio of 0.99 after full adjustment (UK Biobank cohort study). This suggests social isolation has measurable mortality impacts independent of loneliness, supporting the “tip of the iceberg” metaphor.↩︎