Back in 2008, the satirical magazine and website the Onion was in its Golden Age, successfully expanding their content from fake newspapers to fake magazine shows and then, with ClickHole, to parodying the then nascent emergence of social media. Amongst the fake TV segments they produced was one called “Chef Cooks ‘Dream Omelet’ that came to him in a dream”, a screen grab of which is shown at the head of this post. In the segment, a professional chef earnestly advises viewers wishing to replicate his dream omelette to do the following:

- Make sure to use a shoehorn to transfer butter to the pan;

- Ensure the eggs use have the letters ‘WWII’ on them, which can be achieved using a felt tip pen;

- Add lemons that turn into tomatoes;

- Serve with keys and crackers.

This week I decided to watch Megalopolis, Francis Ford Coppola’s much hyped (then much derided) passion project, which reportedly cost him at least one winery.1 Throughout the more than two hour runtime I kept thinking about the Onion sketch above, as I don’t think there’s any better reference point for trying to describe and understand the film.

In dreams, consistent rules of physics and characterisation don’t exist. Instead there are themes and motifs, which blend the humdrum with the impossible with a logic impenetrable to conscious thought. However, despite what happens and is said in dreams being linearly inscrutible, the scenes, themes and motifs themselves can potentially be informative as to the interests and preoccupations of the dreamer. In Francis Ford Coppola’s case, these themes and motifs appear to include:

- New York

- Urban planning

- Powerful old men

- Pretty young women

- The ways powerful old men and pretty young women relate to and predate on each other

- Ancient Rome

- America

- Decadence and decline

- Utopia

- The conflict between pragmatism and idealism

When in a dream, everything is what it is, and why it is is because it must be so. There is no ironic detachment; the subconscious delivers each line and shows each new symbol with weighty earnestness. This dream-like literalism and earnestness pervades Megalopolis; every shot and every word is delivered with complete seriousness, without any knowing looks or winks to the cynics and know-it-alls who may be watching 2. And because of this, for those watching this ever-so-lavish account of a dream, rather than experiencing the dream, the effect can be unintentionally hilarous. Someone hearing an account of a dream, or seeing photos of a holiday, cannot be made to themselves experience that dream, no matter how lavishly those remembered aspects of the dream are recreated for the audience. There will always be aspects of a dream that, for the dreamer, will be inherently sacred and profound - because within the dream the unconscious told the dreamer this is sacred and profound - but that for someone hearing or seeing an account of that dream will not be.

Does Megalopolis work as a film? The answer depends on your definition of film. It’s definitely not a movie, with that term’s connotations of easily digestable storyline, clearly identifiable genre, Campbellesque arc and third act spectacle. But at the same time, it’s stylistically - and occasionally structurally - movie-like. And this can give the impression it’s a bad movie, when perhaps it’s not trying to be a movie at all. But if film is the more permissive of the two terms - and simply means the display of a sequence of still images on a screen so as to give the illusion of motion - then of course it’s a film. Things were shown on screen, for over two hours, and they appeared to move.

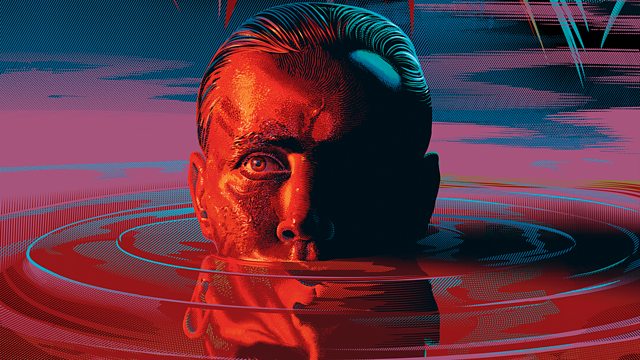

Simpler still: Does Megalopolis work? Again: depends on context and definition. I suspect the film I saw is largely the film Francis Ford Coppola intended to make. Within the series of scenes and shots, there are some that are visually engaging, looking alternately as either colour remakes of shots from impressionist silent cinema, or as prog rock album covers brought to life. Does the ever-earnest leaden dialogue work? No for a movie, or at least most movies produced in the last generation; yes for a dream film. Does the narrative arc work, as in cause us to invest emotionally in a believable protagonist facing perils and payoffs we can understand and find weighty? For me: not really - as the rules and consequences of actions in this world are as inscrutible as in any dream - but then maybe I’m being closed minded by even asking this question.

Is there a better reference point for trying to unlock Megalopolis than the Onion dream omelette sketch mentioned above? Maybe some of Coppola’s earlier films? Perhaps the more psychedelic scenes in Apocalypse Now might work? But then even the most out-there of these scenes seemed more bound by the rules of our known physical reality than those in Megalopolis. Imagine a version of the scene in which Willard stares from his sickbed at the ceiling fan, but then in the next shot is standing upside down on the ceiling, trying to avoid the fan’s blades, which eventually hit him, causing him to shatter into a shower of butterflies. Or the scene in which Willard’s head, caked in green and brown paint, emerges from a black liquid pool, but then in the next shot his head comes to resemble a crocodile’s, but with a shimmering crest at the back of his monstrous skull that pulses with ethereal light. For better or worse, Megalopolis is Coppola’s most untethered film, in which what can and does happen appears little bound to known rules of the real world.

An interesting point of contrast when it comes to this concept of tethering is the work of David Lynch, whose outputs are often more easily understood as nightmare-like than dream-like. I’ve written about what I call Lynch’s shamanistic tendencies elsewhere. The comparison is instructive, I believe, because it highlights how, for all Megalopolis’ strangeness, Lynch is a fundamentally weirder artist and character. For Coppola dreamland and the real world are clearly distinct places, and Megalopolis is a film that seems to take place entirely in dreamland. For Lynch, by contrast, the distinction always appears to be tenuous. Lynch is a character for whom potentially every event and incident he encounters in the real world is pregnant with magic and meaning, a world in which electricity is a mystic force, for instance, rather than a mere instrumental application of known physical laws. Lynch understands the evils and injustices present in the real world, for example, in particular the evil of men’s violence towards women, but reads such incidents as laden with the tells of cosmic forces wielded by barely glimpsed Manichean agents. For Lynch, there is only one world - a strange and beautiful and horrifying and mystical and humdrum world that looks on its surface much like our own, but where those who care to look can see something magical behind the surface. For Coppola, by contrast, and as for most people, there are two.

Given everything discussed above, I’m not sure if the following observation counts as a criticism of Megalopolis or an odd kind of compliment: For parts of the film, I suspect I was asleep.

Footnotes

The wikipedia article reports that Megalopolis cost at least $120 million to make, and has so far received around $10 million in box office receipts.↩︎

The experience of lucid dreaming - dreaming while being conscious of dreaming - may be the exception to this, but the vast majority of dreams are not experienced in a lucid state.↩︎