On Edinburgh’s Brilliant Book boxes

One of the first differences I noticed about living in Edinburgh, as compared with Glasgow, is the presence and use of free book boxes. Little boxes where people are invited both to donate books they’ve finished with, and pick up books they might be interested in reading. Such boxes appear to be both well used and - aside from the occasional spray can tag - well cared for in Edinburgh, whereas (and I really want to be shown to be wrong on this point) I suspect their life expectancy in Glasgow - the time before their doors get ripped from their hinges and contents thrown into the river - would be measured in the days or weeks.

What the free book boxes provide, in addition to free books (and often free DVDs), are windows into past trends. Books that, five or ten or twenty years ago, everyone bought, but now whose entertainment or informational value, and definitely value as cultural signifier, has long been spent for the original owners. So of course, this provides an opportunity for people who didn’t latch onto the reading trends of yesteryear to try, very belatedly, to try to work out what the fuss was about first (or second) time around.

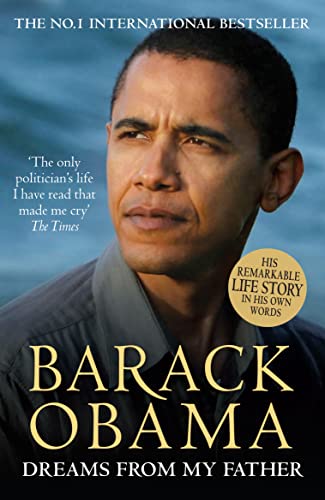

All of which is a contextual preamble for why I’ve now, not ten or twenty years ago, read Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father, the book he was first invited to write in the early 1990s, after becoming the first Black president of the Harvard Law Review, originally published in 1995, then reissued - as attention renewed and intensified with his broader political ambitions and achievements - in 2004. So, what do I think about it?

On the book’s Three Sections

As the subtitle of this post suggests, Dreams From My Father seems to me largely a dialectical treatise on questions of ethnic and cultural identity, from someone whose personal and family history offer legitimate claims to multiple identities. The book has three broad sections - ‘Origins’, ‘Chicago’, and ‘Kenya’ - and in each section a different aspect of Obama’s identity is explored.

The first section, Origins, follows Obama’s childhood, raised primarily by his White American mother in Indonesia, then later also by his mother’s extended family in Hawaii. Capital poor but culturally and cognitively rich, Obama’s earlier experiences read, paradoxically, of those of an upwardly mobile and aspirant migrant family - with grand ambitions and hopes for their future and their children’s future - drawn to the promise of the US as a fundamentally meritocratic society where hard work and talent is rewarded. And indeed, for Obama, it is. However, Obama is a visible minority in Hawaii, and as Hawaii, though off the mainland, is still part of the USA, the apparently totalising binary thinking about race that predominates elsewhere - that one is either Black or White, and if one’s at all black one’s all Black (i.e. the ‘one-drop rule’) - is something that Obama experiences, and so questions of racial identity become ever more salient. Obama leans into this binary, for example chastising another mixed heritage student who describes herself as ‘mixed’ rather than ‘Black’, and becomes drawn ever more into the history and politics of the African American experience.

The second section, Chicago, describes the apotheosis of this quest, and Obama’s work as a community organiser in predominantly Black and socioeconomically deprived neighbourhoods of Chicago, for which he quit a white collar job in which he was rapidly advancing. He’s given a way into this form of applied activism by Marty Kaufman - of New York, Jewish, and in the American Race Binary ‘White’ - but due to his own ethnic appearance Obama is more easily accepted into the communities he aims to serve than Kaufman; he also repeatedly claims or implies his own ethnicity means he has a more genuine connection and commitment to such communities. Here Obama encounters what appears to be the two inseperable sides of the same coin of working class African American experience: on the one hand, the high bonding capital that gives rise of racial solidarity; on the other hand, the low bridging capital that arises from suspicion of outsiders (especially those who are coded as ethnically other), as well as a highly localised and seemingly parochial focus and set of concerns. The call of new white collar career opportunities is heard by Obama, and those Chicago denizens he helped through community organising tend to be both grateful for his support, but unsurprised by his impending departure.

The third section, Kenya, follows Obama as he visits Kenya to meet members of his extended family on his father’s side. He encounters the realities of privation and service quality in a nation substantially poorer than the USA, an apparent (and likely at times genuine) enthusiasm for his visit from persons who can claim some degree of common geneology, but also a sense - perhaps - of being even marked out as Other in Kenya, as a result of his accent, clothing and relative affluence, than he was in either Hawaii or Chicago. He also discovers just how fictitious aspects of the Pan-African Mythos that many African Americans developed and clung onto tends to be, the dream of visiting an ancestral land where almost everyone is Black, and so by extension Black people are more in charge of their own destiny than in the USA. From this comes an explanation for why many of those African Americans who visit Africa leave feeling dissilusioned and disappointed. The issue seems to be that, for the most part, in Africa ‘Black’ is not a meaningful category of belonging. Instead the most salient aspects of an individual’s identity are likely to be tribal, or more broadly extra-familial. In Kenya Obama is not Black as in the USA, but alternately Luo and Western (and so by implication rich).

Neurodiversity

The beliefs that identities should be both more expansive and less determinative appear to have served Obama’s titular father poorly. Despite being both driven and intellectually gifted - a Harvard trained economist - the fortunes of the Old Man, as his extended family referred to him, depended much less on his gifts and experience, and much more on tribal politicking, and whether his tribe’s political power was in the ascent or descent. Once he shifted employment from an American oil company to the government, then his identity as Luo stood him in good stead when the Luo were ascendent, but poorly when Kikuyu were ascendent. And his fortunes worsened further when he alienated both Luo and Kikuyu alike by arguing against tribalism, and for a broader Kenyan identity and solidarity. The Old Man - who didn’t live long enough to really deserve the moniker - died fairly soon after the tides had started to turn back in his favour, leaving a small estate but - as we now know - a world-changing genetic legacy.

When it comes to the search for the links between Obama’s (the Second’s) heritage and identity, one of the most obvious answers seems almost to be hiding in plain sight, in an extended oral geneological account near the end of the book. Obama (the son) was extraordinarily capable and driven because Obama (the father) was extraordinary capable and driven, and Obama The Father was this way because his own father, Onyango, was perhaps even more extaordinary:

Even from the time that he was a boy, your grandfather Onyango was strange. It is said of him that he had ants up his anus, because he could not sit still. He would wander off on his own for many days, and when he returned he would not say where he had been. He was very serious always - he never laughed or played games with the other children, and never made jokes. He was always curious about other people’s business, which is how he learned to be a herbalist. You should known that a herbalist is different from a shaman - what the white man calls a witch doctor. A shaman casts spells and speaks to the spirit world. The herbalist knows various plants that will cure certain illnesses or wounds, how to pack a special mud to that a cut will heal. As a boy, your grandfather sat in the hut of the herbalist in his village, watching and listening carefully while the other boys played, and in this way he gained knowledge.

When your grandfather was still a boy, we began to hear that the white man had come to Kisumu town. It was said that these white men had skin as soft as a child’s but that they rode on a ship that roared like thunder and had sticks that burst with fire. Before this time, no one in our village had seen white men - only Arab traders who sometimes came to sell us sugar and cloth. But even that was rare, for our people did not use much sugar, and we did not wear cloth, only a goatskin that covered our genitals. When the elders heard these stories, they discussed it among themselves and advised the men to stay away from Kisumu until this white man was better understood.

Despite this warning, Onyango become curious and decided that he must see these white men for himself. One day he disappeared, and on one knew where he had gone. Then, many months later, while Obama’s other sons were working the land, Onyango returned to the village. He was wearing the trousers of a white man, and a shirt like a white man, and shoes that covered his feet.

In modern terminology, therefore, Obama’s grandfather might be described as neurodiverse, drawn to understanding how technologies work and how he could make these technologies work for him. The same orientation towards the world that led to an interest in the tribal technology of herbalism also led to understanding the advanced technologies - literacy, numeracy, administrative systems, transport, weaponry - of these strange and sinister colonialists; advanced technologies that he quickly came to understand were all that fundamentally differentiated these people from his own, and which were the source of the power inbalance between the two peoples. Like a one-man Japan, Onyango appeared to devote much of his life to understanding, mastering and applying these colonial technologies, but ultimately with a view to narrowing the power imbalance between Luo and colonialist, and so reducing the ease with which the latter could exploit and subjugate the former.

And so, this strange herbalist begot a Harvard educated economist, and the Harvard educated economist begot a Harvard educated lawyer, who became the 44th president of the USA.

Dialectics and the Law

In the subtitle of this post I’ve described Dreams from my Father as dialectical. It’s perhaps worth clarifying what I mean by this, as well as why Obama’s dialectical treatment of issues like identity appears to fit with a bias towards system thinking that appears, in part, to have a geneological component.

A dialectical argument involves a Thesis, and Antithesis, and then a Synthesis. A Thesis is a clearly expressed and pure position on something, an Antithesis is an equally clearly expressed and pure position on something that appears to be incompatible with the Thesis; and a Synthesis is the consequence of, nevertheless, finding a means of reconciling both Thesis and Antithesis.

For a trained lawyer, dialectical argumentation is something that likely quickly becomes second nature. What is the Thesis but the case put forward by the prosecution? And what is Antithesis but the case put forward by the defence? And then, to the extent not all charges have to be unanimously proven or not proven, what is a judge’s ruling but a Synthesis of the facts and arguments as put together by both sides?

Law, at least in the Common Law tradition as practiced both in the UK and USA, is accretive and incremental. The laws as passed by primary lawmakers, i.e. politicians, are broad sketches. The precise blueprints which emerge from trying to operationalise these sketches come from case law. What does the broad principle actually mean in this circumstance? And is there an existing piece of case law that’s similar enough to what we’re looking at that, in this case, we have the blueprint and not the sketch? As the number of test cases increases, so does the behavioural resolution of society. Eventually, there’s a memory and a map for how society should behaviour, fairly and responsibly, for every social eventuality.

For someone practiced in this tradition, this mode of reasoning, the concept that “the arc of history bends towards justice” just about makes sense. By allowing claims and counterclaims to be expressed as clearly as they can, and finding and supporting impartial judges who can weigh and synthesise both sides, something like progress just keeps happening. This is the cautious hope of the progressive centrist, and differs markedly in its incrementalism from the radical conception of history and dialectics associated with Marx through Hegel, in which the arc of history doesn’t so much bend towards justice, as break towards justice, the thesis of each epoch crashing down violently under the accumulated weight of its antithetical contradictions. Bending is gentle change; breaking is violent change.

Dreams (and Nightmares) of a Radical

Dreams from my Father appears frequently to try to flesh out, understand, sympathise with and inhabit a range of distinct - and apparently contradictory and irreconcilible - notions of self identity: White, middle-class, internationalist; Black, urban, working class; African, Kenyan, Lou; a father’s son, a grandfather’s grandson, a mother’s son. Obama’s preferred first name changed over the course of the three sections: From ‘Barry’, to ‘Barack’, then back to ‘Barry’ again. This quality of bringing intense, analytical curiosity and equinimity towards each facet of a complex question, then offering a position of synthesis without tarnishing or distorting any facet, was perhaps one of Obama’s greatest gifts as President.

When it comes to race in the USA, however, the cognitive cultural dominance of the One Drop Rule - that if one is at all black one is All Black - perhaps meant that the part was sometimes conflated with the whole. Rather than genuinely accepting Obama as an extraordinary man of many facets and identities, he was ‘just’ the USA’s First Black President. Many people, it seemed, couldn’t see beyond this concept, with both supporters and critics alike thinking the simple fact of being a Black President connoted a much greater degree of radical departure from the past - a breaking not a bending of the arc of history - than this studious, cautious lawyer with a baritone voice would ever have been willing to deliver.