Warning: Moderate spoilers for Civil War and Warfare.

A few weeks ago I went to see Warfare, the latest film from Alex Garland, whose previous film, Civil War, marked a departure from Sci-fi and towards more grounded speculative fiction. For Civil War, Garland want to achieve a strong sense of realism about the conduct and experience of war. Civil War was largely position from the margins of conflict, following a small team of war journalists trying to piece together enough of a sense of what was happening as to be able to report something informative and accurate to readers, a task challenging tiven the constant fog of confusion that had descended on the ‘United’ States, and hazardous becuase in this civil war there seemed to be no clear rules agreed about who was a legitmate target and who could peass peacefully.

A scene midway through the film brought both the confusion and hazard to focus: a small armed forces unit the team of journalists happens to be near gets fired upon from somewhere over there. Which side or faction the combat unit fights for isn’t clear; which side or faction the enemy forces represent also isn’t clear. For all the viewer knows (I think) this could be an instance of ‘friendly fire’. All we, the journalists, and the combat unit do know is that the bullets coming from over there represent a threat; and from the combat unit’s perspective it’s implicitly understood that such threats need to be mitigated or neutralised: years, months, or possibly weeks of training has drilled the unit into a standard response to such situations, a profocol for dealing with such situations has been triggered, and fire is returned.

The film ends with a military coup, an assault on the Capital and removal (read: execution) of a head of state some sides or factions consider legitimate and others not so. Throughout the film’s war scenes there is a focus on both experiential and procedural verisimilitude: combat units are well drilled professionals following well-rehearsed scripts for engagement. This was not the standard Hollywood Action fantasy in which one side who cannot aim is defeated by a one man army with preternatural luck and skill: Rambo is nowhere in this story. Instead, each troop undersands the inherent hazard in their job, but also proven tactics to mitigate such risks to their own side. Suppressive fire is employed so continually as to overwhelm the viewer’s senses, the sound design bringing out the explosive enormity of high caliber munitions, the sights and sounds of gunfire intended to minimise opportunity to return fire more so than take out specific targets: better a thousand of our rounds miss them than one of their rounds hits us. Once the White House is breached the nature of combat changes: a small team becomes a superorganism, wordless gestures turn training, troops and equipment into a mobile fortress, without blindspots, vigilant to threats from all directions.

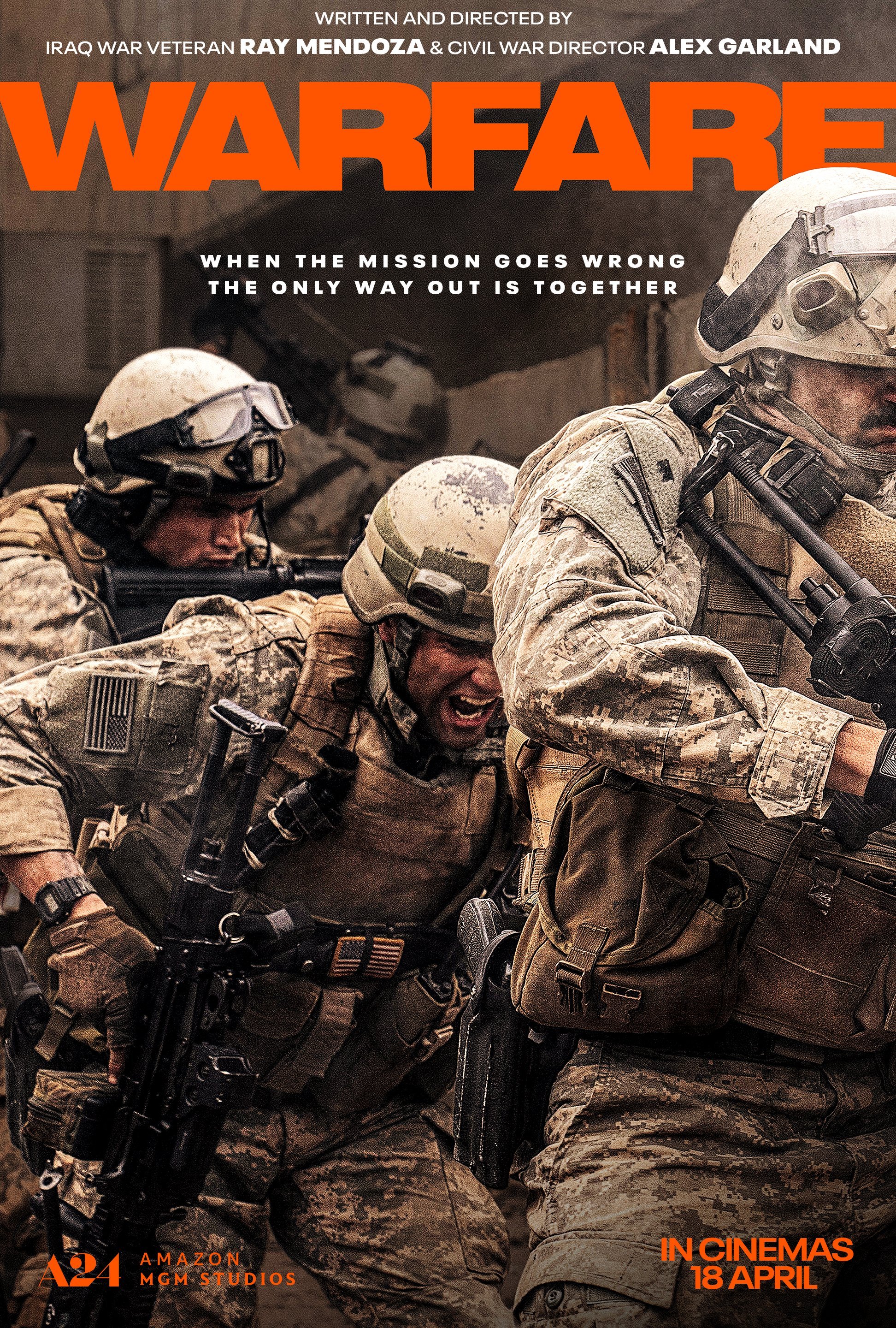

To bring this sense of verisimilitude to Civil War, Garland employed Ray Mendoza, an Iraq War veteran, as military supervisor. Garland found Mendoza’s expertise in, for want of a better term, warcraft, and experiences of combat, so interesting and important as to lead to a wish for further collaboration. Warfare was the result of this desire to collaborate further, with Mendoza co-writing and co-directing with Garland.

Whereas the scope for Civil War is continent-wide, and its story distopian speculation about a not-implausible future, Warfare’s scope is intentionally constrained and historically localised. The film defines itself as an attempt to recreate, as accurately as possible, an ‘incident’ of warfare, that was for a number of those involved life-altering in its mental and physical effects. The ‘incident’ took place in Iraq, in 2006, to a platoon that included Mendoza. Due in part to traumatic injuries suffered by many involved, and the effects such intense experiences can have on memory and the perception of events, the story is based on a tapestry of accounts and recollections from all involved, each individually partial and incomplete, but together likely the most accurate and authentic detailing of how events unfoled, and how they were experienced, it is likely humanly possible to reproduce.

The incident shows the results of when events don’t go as planned for the platoon, in some ways go from bad to worse. But iltimately, in some ways amazingly, and in large part due both to the troops’ ability both to execuate plans under the most challenging of circumstances, and to adapt and improvise when the situation demands it, there were no platoon fatalities, ‘only’ grievous and life-changing injuries.

Warfare is apolitical, which in the modern age may be an especially unpopular political position to take. The platoon are young men, set apart from the civilising and moderating influence of polite society. But they are also highly trained, highly drilled, and lavishly well resourced, professionals. As in Civil War, the sublimation of the individual, the conversion of individual soldiers into a Superorganism, is on full display. The troops are shown to have incredibly detailed understanding of the craft of warfare, the mastery and internalisation of processes and procedures, the if-then rules and memorised checklists of what ssteps to take, by whom, in the event of X, Y or Z. And as in Civil War, with access to overwhelming resource and firepower, the calculus again being that is is better to lose ten thousand bullets than a single platoon life, is shown to its full destructive extent.

Before watching the film, I heard a review from Mark Kermode. In summary, Mermode offered a hackneyed three word cliche: “War is Hell”. Before watching the film I fully expected to draw the same conclusion. However, on seeing the film, and giving myself a little time to process the experience, my brain found itself drawn to a very different, albeit equally hackneyed, three word cliche: “Band of Brothers”.

Though it seemed to be a strange, even pathological, manifestation of it, the strongest underlying sentiment on display in the film was love. In particular, the psychological and emotional changes that can occur when a small group of young men are trained together, brought together, and find themselves in circumstances where they must survive together, or die together. In Warfare, the injury to one troop is experience as an injury to everone. In the most grevious, terrifying and chaotic of circumstances, ths strongest motivation that drives an individual to risking their own life was to save and preserve the life of a colleague. This - (pseudo-)fraternal love - was the hidden ingredient to the Superorganism behaviour first dispalyed in Civil War. Training and resourcing was a necessary but not sufficient condition for a group of hormonal teenabge boys and twenty-something men to become a cohesive fighting force, a Superorganism that puts its own survival, ultimately, ahead of all other aims and objectives. 1

This kind of love is not an unalloyed good, however. This kind of love is conditional and bounded: the love extends only to the platoon itself, not the Iraqi translators they work with, nor the innocent civilians whose houses the platoon requisition and ruin, nor the broader community that is shot at, nor their street which is turned into a rubbled warzone. This kind of love, together with the lavish resources that the platoon can call upon, can be an extremely powerful force, not necessarily for the good. At the end of the film, after the platoon has departed with most of their limbs and faculties intact, the residents and combatants, whose street the platoon had turned into a warzone, emerge from the devastation and rubble caused by the last hour of fighting. How many enemy compatant casualties has the platoon ‘scored’? It’s unclear. Have any of the residents’ ‘hearts and minds’ been converted by the platoon’s actions, and if so in which direction? The answer to this is probably clearer.

Warfare is an intentionally mypoic film telling an account - as good an account as can ever be told - of a particular incident from a particular point of view. This is by design, so cannot be a flaw if the film is taken on its own terms. There is, of course, a broader context to ‘the incident’, but these are well known and well rehearsed. Meshing the microscopic perspective of Warfare with the macroscopic perspective of whether it was ever wise to invade Iraq in the wake of 9/11 (especially when most of the ringleaders were from Saudi Arabia, which was never attacked) is a question orthogonal to that of whether those US troops who were sent to Iraq acted, by and large, with discipline, professionalism, and the myopic love of comradeship. Perhaps all we can conclude, ultimately, is that strategic misadventure and incompetence can be implemented with tactical precision and courage.

Footnotes

In the film, the only time the platoon were are shown to breach standard operating procedure - to bend or break the rules - was to illegitimately authorise a second attempt to pick up the casualties.↩︎