Preamble

Here’s something that’s differently nerdy. Some thoughts on the enduring and childish appeal of Robocop as a character and concept, lifted largely from some notes I made on Obsidian (which also uses Markdown).

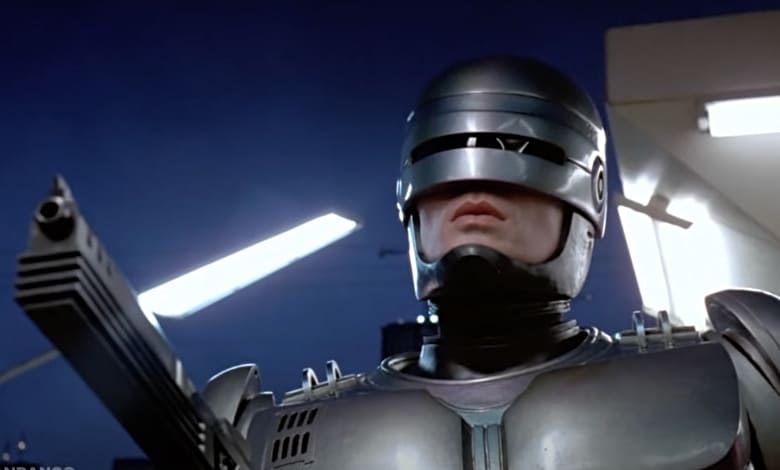

Notes on Robocop

Went through a Robocop phase. First film is good. Second film is adequate fan service (by Frank Miller), though unpleasant in terms of how it makes a boy a main antagonist. Reboot is terrible.

I think this was inspired by seeing footage for the Robocop game Rogue City. Also remembered discussion about how in the original film Robocop’s death and resurrection is modelled on Jesus. It’s definitely true his death is a ‘passion’ (modern equivalent: torture porn?), and that his suffering at the hands of sadistic tormenters fits this pattern.

In the first film there’s also the sense of the protagonist reclaiming his humanity. Murphy’s memory is wiped, but through force of will he brings himself to remember who he was, and to identify as Murphy. That’s the last line. He’s thanked and addressed by the Old Man as a person, not as property That’s the arc: becoming human again.

By contrast the reboot started with Murphy knowing who he was, though the scientists can modify the extent to which his feelings or programming are in charge. There’s a plot about police corruption and selling weapons illegally, and plenty of exposition from scientists where they try to shoehorn in cod-philosophy on personhood and free will, but this felt like ‘filler’ between a series of action sequences, which were much faster but also much less weighty and visceral than those in the original.

In the original Robocop is a bullet sponge. He was slow, apparently unfeeling. Though this might be partly a function of Peter Weller not having a great deal of mobility when wearing the suit, it also feeds into the central character arc: robots don’t feel; people do.1 Robots aren’t vulnerable as people are. As Robocop becomes damaged, he becomes more vulnerable, and his face becomes visible. Vulnerability is necessary for humanity to be restored. Robocop’s suit makes him a superhero, an adolescent boy fantasy of massive strength and power, but it also makes him a prisoner, trapped and entombed.

Again, by contrast, in the remake Murphy has lost less. He still has a human hand, still has his memories and sense of self, and still has all the speed and mobility he had as a person, only more so. He doesn’t have an arc, he has perturbations and wobbles.

Let’s think some more about why Robocop is an adolescent, or even pre-adolescent, fantasy. Firstly, it appeals to a kind of crude creativity of combinatorials: take two things that are familiar, combine them, and make something unfamiliar. With only a limited number of schemas, even a young child can wonder what happens when they are combined, and feel excited and proud about bootstrapping from everyday experience to pure fantasy. Like the distinction between animal, vegetable and mineral, ‘man’ and ‘machine’ are different primary colours, and seeing the concept of Robocop may be for a young child like seeing red and blue make purple for the first time.

Second, there’s the power fantasy. Within this, there’s the sense of seeing someone who can play an action game and be allowed to ‘cheat’. The roles of an action game, involving shooting, must include that, once shot, the player must ‘play dead’. But in Robocop is a fantasy of a character who’s still allowed to shoot others whilst being able to ignore when others shoot him. Robocop presents a fantasy for a young child of playing a game where you can do things that no-one else can, because you’re more special than everyone else.

I suspect that’s why, even though Robocop was clearly unsuitable for children, the concept of Robocop appeared to have so much appeal to children. There’s something inherently childish about seeing such a pure chimera rendered on screen, and the possibilities and affordances of this chimera are signalled so brightly from the images alone that the (adult) source material does not need to be consulted.

Again, this seems to be yet another reason why the remake did not work: 2014’s Murphy was not machine enough. The suit did not make him clearly ‘other’ enough. Even though the graphic violence was toned down so that in theory children could watch, the lack of schematic purity in the ideal types being mixed meant the pleasure of seeing primary colours being mixed, in the way the original so effectively managed, was muddied and diluted.

Footnotes

Alistair Gray’s Lanark played with a similar idea, in the form of Dragonhide, a magical realist representation of dermatitis, emotional distance, and lack of outlet for artistic expression. Too much Dragonhide, the book warns, causes sufferers to become unable to move, and unable to vent, their heat and energy, without expression, eventually causing them to boil to death!↩︎